And One Day We Will Rest

Bertha loved to dance.

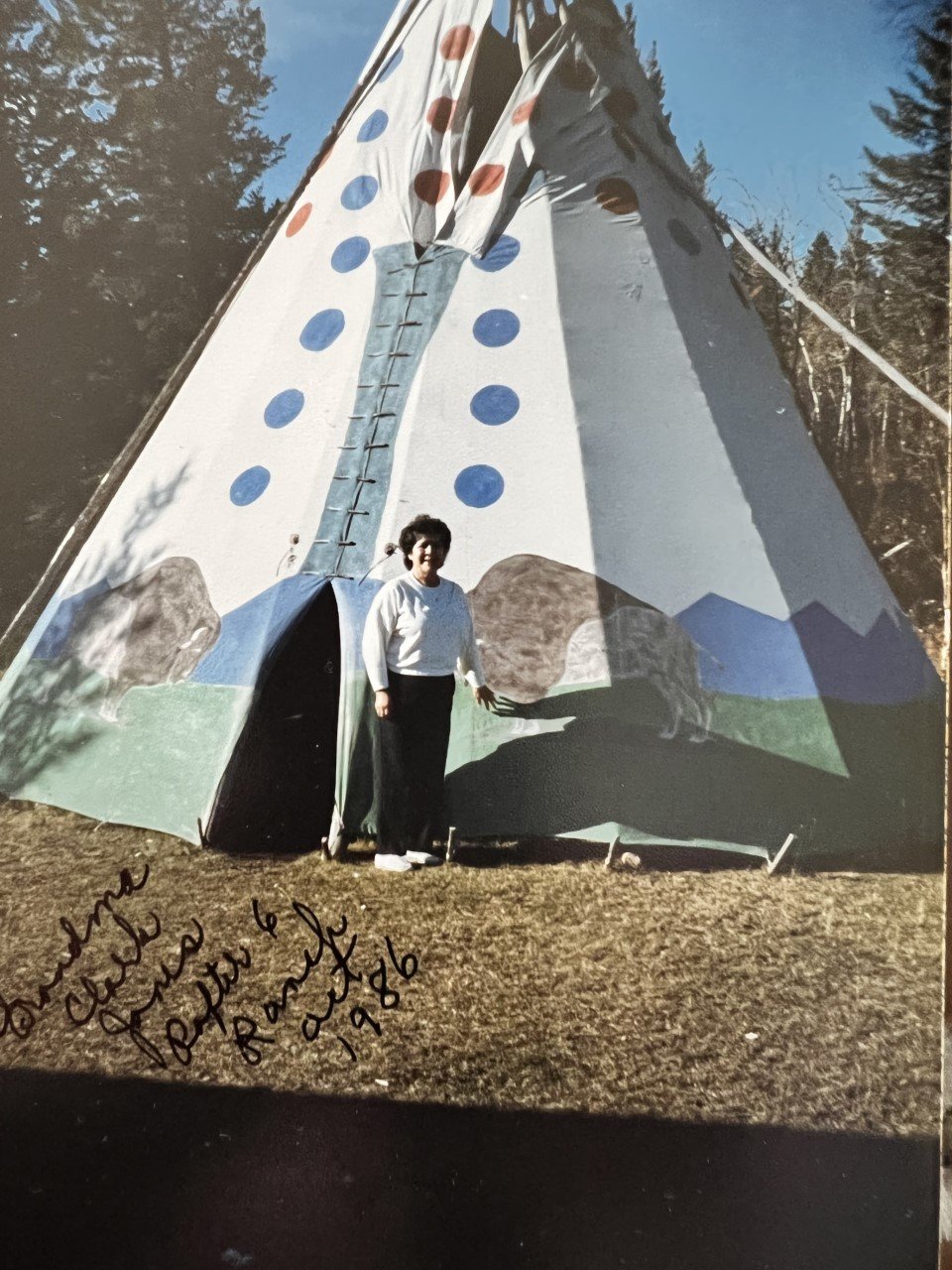

This picture is the cover photo of an album she gave me when I was 3. It has letters, photos and a gift of a $2 bill from her. This is not a picture of her dancing but it is one of my favourites.

Her father played the fiddle and also performed the jig. When her father was not on the trap line in the fall seasons, her homestead was filled with the joy of music and dance. As the fifth child of fourteen, Bertha learned early the importance of hard work, and also how to speak up.

Bertha Clark (nee Houle), now deceased, lives on in her accomplishments and well-deserved honours. She was an athlete, a Veteran, the first president of the Native Women's Association of Canada, an Elder, and a proud Cree Metis woman. Bertha was also my grandmother.

I wanted to imagine and share one of the many turning points of her life, and one of my favourite stories of her outspokenness. The following incident is a retelling from my imagination. The events were real. The details and timelines I have filled in with artistic license. I've many times imagined this incident to be one of the catalysts for her activism. This is the story of when Bertha's joy of music and dance was pushed up against by misogyny and racism.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Bertha prepared for an evening of dance at the Oil Sands Hotel in Fort McMurray. It was a warm summer evening in the early 70s. Fort Mac was experiencing 'a boom'. Suncor had just opened a plant a few years ago and folks were coming to the city in droves. Bertha had moved to the town to get a job in the camps as a cleaner. She worked hard. And on her nights off she wanted to dance.

She strapped on her white, platform sandals. In the mirror, she teased her black curls up from the top of her head, and ran her tongue across the front of her teeth to erase any signs of stray lipstick. She grabbed her cash and keys, locked up, and then dashed down the apartment steps.

Out front, her eldest daughter, Gail was waiting in a powder blue, Lincoln Continental. Some rust around the rims from salted, winter roads, but otherwise the car was an unspoiled dream.

Bertha had a melodic, feminine voice, and Gail had inherited that from her. The pair sang along to a Sonny and Cher song on the car’s 8-track player as they made their short way through town toward Main Street. Gail chose the Sonny parts because she was dating a man named Sonny.

“How is work treating you?” Bertha asked Gail.

“Fine. They keep putting me on the late shift at the diner, but I got upgraded from scrubbing dishes to serving, so some tips should come my way soon.”

Bertha stared forward out the car windshield, she chewed her lip a bit.

“Something on your mind, Mom?” Gail asked.

“That manager has no respect for Native women, just be smart is all I’ll say. Don’t turn your back to him and the tip jar.”

“Oh, Mom. It’s not like that. Plus, I won’t be there forever. Sonny got a camp job and we’re going to save up to get a place in Athabasca. I could take some courses at the new university.”

“Education is a good idea, but how does Sonny feel about it?”

“He knows it’s not school like the nuns ran when he was a boy. But yea, he may take some convincing.” Gail replied.

“Just make sure you aren’t relying too much on his money. And while this car is beautiful, I’d stop making purchases like this too. If you’re serious about an education, and starting a family.”

“Thanks, Mom. I’ll try my best.”

When they rolled up to the hotel they could hear the hum of the music escaping through the walls. The band was playing a Johnny Horton song. Bertha and Gail strode in during the middle of ‘North to Alaska’. Bertha began to clap to the beat and stomp her foot and sing along “Where the river is windin’ big nuggets they’re findin’

North to Alaska go north the rush is on

North to Alaska go north the rush is on”

How fitting the song about the Alaskan gold rush being played during an oil boom in Fort Mac.

Gail and Bertha threw their jackets over some chairs at an empty table along the dance floor, and then joined the crowd to encourage the band.

After a few songs, and with her throat dry from singing in the smoky air, Bertha decided to go to the bar for a drink. She heard the band get into their next song, the umistakable twang of that Hank Thompson hit, then the lyrics loud over the instruments “There's a Salmon-colored girl who sets my heart a-whirl…”

Bertha yelled to get the bar keep’s attention, “They shouldn’t play this song.”

“OOGA-OOGA MOOSKA which means that I love you.”

“I want them to stop this right now!” She demanded and banged her fist on the bar top.

The barkeep handed her a drink and mimed for her to calm down.

“Then I take her hand in mine and set her on my knee

The Squaws along the Yukon are good enough for me”

Bertha ignored her drink on the bar and charged to the stage.

Out of the corner of her eye, she could see Gail sitting stiff and quiet at the table.

She approached the singer. He was crooning the last lines. He looked down at her on the dance floor, and she stared up at him, her hands on her hips, chin jutted out.

“That song is offensive to Native women.”

The singer raised his brows, and smirked, “What’s offensive?”

“The word, squaw, is a nasty term for Native women.”

“Well, I didn’t write the song, lady, I just sing it.”

“Well you shouldn’t. It makes me uncomfortable, and it makes me feel unwelcome here. And not just me, but other women.”

Bertha gestured to Gail who was sitting at the table drawing water lines on the surface with her straw and avoiding her mother’s eye. And there were a few other women in the space who had stopped dancing and sat at their tables, or who had gathered their coats and purses to leave.

The singer adjusted his cowboy hat and nodded to Bertha.

“You’re right. I hadn’t considered what the song meant. I am sorry. We’ll pull it from our set list.”

Bertha nodded and then made her way to sit down with Gail.

“You’re always standing up for everyone, Mom. It’s just a song.”

“It doesn’t stop at just a song, Gail. My whole life I’ve seen what happens when things go unquestioned. And it’s not just because we are Native that we must speak up. It’s because we are Native women.”

Doesn’t it get exhausting though?” Gail asked.

“It does. And it will for you. But one day your children, or your children’s children, won’t need to fight, and then, we will rest.”

____________________________________________________________________________________

My grandmother never rested.

The above was a small example of the hardships and injustices she faced and fought her whole life. Sure, I could list and go into detail the most horrific and catalyzing abuses she faced, but I find this story to be one of her most mobilizing. How simple an example it is for allies to pay attention to this insidious racism and call someone in -- give Indigenous women an opportunity to rest.

In the process of writing and imagining this scenario, I leaned heavily on my aunt Gail Gallup (nee Clark). I would be remiss to not highlight that she is also an inspiring woman. Gail raised two beautiful daughters whom I love so much. And Gail served as the President of the McMurray Metis Association volunteer council for several years (most notably during the 2016 wildfires).

I want to thank Gail and my grandmother for their legacy of leadership and inspiration. I also want to thank CDLI for providing a platform to share their stories and voices, and for continuing to challenge me and others to be our best selves and do our best work.

Written by Jessica Clark